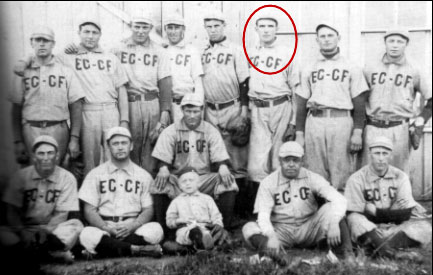

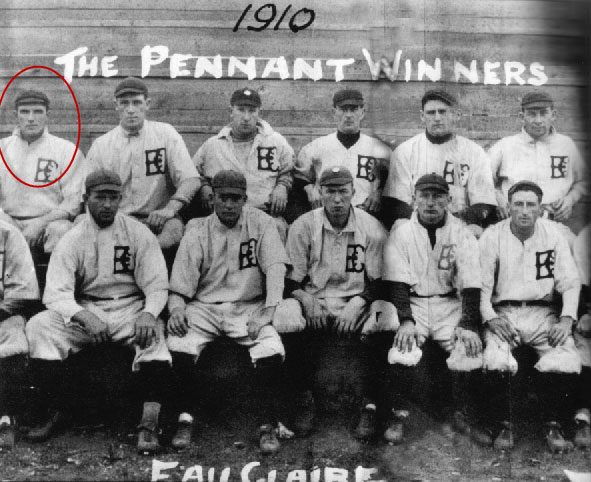

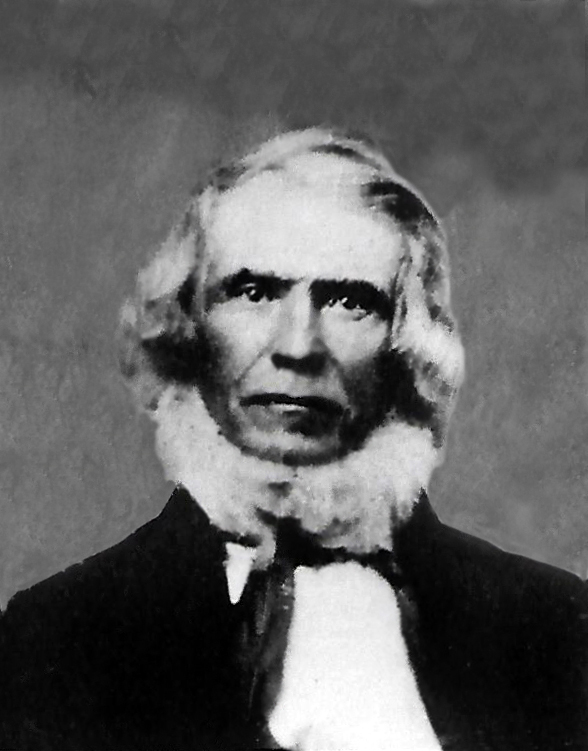

A distant cousin shared this funny story with me recently. He also shared the picture of Richard “John” Hall.

On Saturday the 6th day of January, 1838, near the same spot where a quarter of a century before the first settler in the Town of Ellington felled the trees and erected his rude log cabin in the forest , originated one of those amusing, yet at the time, seemingly serious events, that spread consternation among the then inhabitants of the eastern part of the county. The winter was one of extreme mildness and on the morning of the day of which I speak, the sun arose in a cloudless sky and its rays lay with almost summer warmth upon the bare earth and brown leaves.

Nearly a mile west of Olds’ Corners, on the Cattaraugus County line, and on the old Chautauqua Road, in a little log cabin, lived one Eldred Bentley, Jr., with his family, among whom was a daughter named Mercy, a simple-minded girl. Eldred had married a daughter of one John Niles, whose wife had succumbed to the hardships of life, and the old man was then making his home with the Bentley family. His conduct was not at all times exemplary and Olds’ Corners in those days afforded tempting opportunities to the old man’s appetite which met with feeble resistance upon his part. It is supposed he had taken an early morning walk to the tavern and upon his return had sat down by the roadside on the sunny side of a log to enjoy the open air and warm sunshine. The external and internal warmth, both conspired to lift from his soul the oppressing cares of life and he soon passed into a happy slumber. At this opportune moment an Indian, from the neighboring Cattaraugus Reservation, came on foot along the highway and spied the old man resting by the roadside. He stopped momentarily, evidently taking in the old gentleman’s condition, which no doubt inspired his native thirst for the white man’s “fire-water;” and whether he instituted a search upon Niles’ person for the coveted fluid or not, at all events underneath the old man’s outer garments showed conspicuously a red shirt.

As the Indian turned to pursue his journey, the girl Mercy appeared not far off and spying the Indian and her grandfather’s form half reclining upon the ground, with his red shirt made more conspicuous as he lay in the bright sunshine, she in an instant, in her excited imagination, transformed the red shirt into a blood-stained garment and peopled the woods with savage Indians.

Without a second look she ran to Perry Bentley’s, a near neighbor, where her uncle, Richard J. Hall, commonly known as John Hall, who lived about one and one-half miles west on the same road, happened to be calling that morning on horseback. She hurriedly told him that her Grandfather Niles had been killed by the Indians and that the woods were full of them below the house and they were murdering all the white people. Hall, startled by the story of his niece, and not stopping to learn of its truth, sprang upon his horse and started upon a run west along the old Chautauqua Road, calling loudly at every house that the Indians were down in the Bentley neighborhood and were murdering all the white people.

His course led up the hill which he pursued until he reached his own home, which was a log cabin near the top of what was then called “The Big Ridge,” or, “Mutton Hill.” Nearly opposite Hall’s house was a new frame dwelling owned and occupied by Benjamin Ellsworth which is still standing and habitable to this day. Under this house was a commodious cellar, and an arrangement was quickly made with Ellsworth, after acquainting him with the gravity of the situation, whereby the women and children of the neighborhood should there congregate and take refuge in the cellar while the men, who were supposed to be made of sterner stuff, should be summoned from far and near to give battle to the Indians at this point. On the score of strategy the place was well chosen. No more commanding position could have been selected in all that section of country. Indeed, from this point an extended view can be had of the Valley of the Conewango for many miles and beyond of the distant hills of Cattaraugus. The sloping hillsides in every direction made approach doubly difficult by an advancing foe, beside, a little cemetery had been started near by where the bodies of the slain could be conveniently interred.

A few rods west of Ellsworth’s was a log schoolhouse, the first built in the town, where school was then in se10sion. The little flock were quickly transferred to the cellar, save one of the larger boys, who was dispatched to the home of Captain Moses Ferrin about three-fourths of a mile north in the Town of Cherry Creek, with request that he warn out his company of militia in that town and come with all possible haste to the place of rendezvous at Ellsworth’s.

After making these preliminary arrangements, Hall continued his ride on horseback westward down the hill at breakneck speed, warning every settler of the impending danger and to proceed with their families immediately to Ellsworth’s for safety and defence. Consternation seized the people; some were just sitting down to their midday meal, but sprang from the table, collected their firearms, if they had any, and a few personal belongings, leaving their meal all untouched, and with their wives and children hastened to the place of meeting. An eye-witness of this impromptu gathering on the hill, discussed years afterward, with much levity, the personal appearance of some of the women on that occasion, showing that no time had been wasted in the preparation of their toilet. Dressed in short home-spun skirts with pantalets and boots, some with their husbands’ striped jackets and old hats and caps, with hair flying, pulling along in frantic haste their frightened and sobbing children, in their wild rush for a place of safety. ‘Tis said one young lady appeared upon the scene with three hoods upon her head, a pitchfork in one hand and broad-axe in the other, and the strangest thing of it all was that she was unable to explain how she acquired the outfit. Almost as much disorder and confusion characterized the men who gathered on that memorable occasion; some had guns with ammunition, some with no ammunition, some with swords, some with pitchforks and butcher knives, indeed anything that might be turned into a weapon of defense. One man, who no doubt believed in fighting at close range, appeared with six butcher knives bristling from his person. So the inhabitants gathered as the news spread, and in the meantime Hall was speeding westward to the Bates Settlement, in the Clear Creek Valley. Here Carey Briggs was teaching school and it was the noon hour. He sat quietly in his schoolroom enjoying his midday lunch when he observed an unusual commotion among the children in the yard, and that they were fleeing toward their homes with all possible haste. Soon a neighbor appeared and informed Mr. Briggs of the cause. School was over for that day and the master, not with rod and rule, but with a pitchfork over his shoulder, joined the party marching for the “Big Ridge.”

From this point westward the news was carried by fleet-footed messengers to Gerry, Charlotte, Arkwright and other neighboring towns with orders to the several companies of militia to gather for battle. To the story was added the further intelligence that three thousand Indians from Canada had landed at the mouth of Cattaraugus Creek and had made their way over into the Conewango Valley and were killing and scalping the white people as they went, and that Dwight Bates and family, who lived as near as the Bates Settlement had already fallen victims to the wily foe. Many a home was barricaded against the invaders, while the thoughtful housewife hung her kettles of water to the swinging crane in the fireplace, preparing to scald the red-skins upon their approach.

Hall, changing his course at this point, proceeded eastward down the valley toward the village, heralding the news at every house he passed, and if by chance he met a doubting Thomas he gave expression to his offended dignity by commanding such, by virtue of his office as Justice of the Peace of the Town of Ellington, to hasten to the place of conflict, armed and equipped for battle. (It might here be added that Hall had come into office as Justice just five days prior to the happening of this event) The veteran miller, the late Henry Wheeler, decided that the place of safety for his little flock would be in the wheel-pit under the mill, while he stood picket on the outposts. The village schoolhouse then stood a little west of the “Center,” as it was then called, on the road traveled by the fleet messenger. The late Lorenzo D. Fairbanks was teaching and school was in session; and this is what one of the pupils present on that occasion, the late Hon. Albro S. Brown, in a published article years afterward had to say about Hall’s appearance there: “A man rode up to the schoolhouse door and in a stentorian voice demanded a hearing. The teacher and several of the larger boys rushed to the door to ascertain the cause. There we were confronted with a black horse, flecked with foam and besmeared with mud, its rider apparently filled with alarm and consternation, and in a hasty, loud and tremulous manner, delivered this strange and startling message: “Turn out! turn out! the Indians are upon us! The women and children are to be taken to the village for safety, and the men in arms ready for action are to assemble at the house of Benjamin Ellsworth!” And away went the messenger with the speed of the wind, spreading the startling news to the right and the left.” It is needless to say that the school was closed for that day and the frightened children fled to their homes for safety.

Hall, upon his arrival at the village, hastened to inform Captains Enoch Jenkins and Ebenezer Green, of the militia, who immediately began to get together such members of their respective companies as they could readily reach, and at the same time urging the citizens who were provided with arms to join their commands.

There was a wild rush for firearms and ammunition for defense or aggressive warfare. Some of the inhabitants chose to remain and guard their homes and the families of such as took the field, while others proceeded in companies and squads, cautiously toward the seat of war.

Down the valley to Clear Creek—then called “Tapshire”—fled the rider of the black horse, already grown hoarse from incessant shouts of warning, until he arrived at the home of Col. Noble G. Knapp. Knapp held a commission from Gov. William L. Marcy as Colonel of the Two Hundred Eighteenth Regiment of Infantry, composed of several companies scattered about in the adjoining towns. Hall lost no time in making known to the Colonel the gravity of the situation. It is said the Colonel was visibly affected and declared he would need to make some necessary preparation before starting, as it was “the custom of the red-skins to always kill the officers first.” It is also related, concerning the truth of which the writer does not vouch, that the Colonel took down his sword and proceeded to grind it, but that his nervous hands bore more heavily on the back than the front of the blade, and that before his departure he bade an affectionate farewell to his wife and children, adding to the latter that “their papa was going away to fight the Indians and might never return.” Finally the Colonel, with such of his comrades, who as the news spread, had come to his assistance, proceeded cautiously toward Olds’ Corners and to the scene of the conflict. Hall who had preceded him and warned the people along the way and nearly completed a circuit of a dozen miles or more when his poor beast, overcome by the fatigue of the journey, fell to the earth and expired—the only recorded death resulting from the “Indian War.”

In the meantime at Ellsworth’s on the “Big Ridge,” recruits were arriving from the country covered by Hall in his flight, and all was bustle and confusion. The vigilant eyes of the settlers there assembled scanned the outskirts of the neighboring woods, expecting every moment to see the red-skinned savages emerge from their secret hiding places and hear their blood-curdling war whoops. Ellsworth, upon reflection, not just liking the idea of having his house turned into a stockade and thus exposing his wife and six children to possible death and torture, concluded to load them into his ox cart and move on west, leaving his neighbors to give battle to the enemy. He had no sooner commenced to put this plan into operation than the rest of the party gave him to understand that if such a move were attempted they would shoot his oxen on the spot. That settled the matter and restored his heroism. About this time a lone horseman was seen leisurely approaching along the road from the direction of the supposed enemy. All eyes were intently watching his movements. Speculation was rife as to what it all meant, that any living person could exhibit such supreme indifference in the face of imminent danger. His actions were regarded with the keenest suspicion, and upon his arrival, he was immediately the center of a questioning crowd. He expressed great ignorance and surprise at the wonderful stories related to him by the people there assembled, and hastened to assure them that he had personally passed the “dark and bloody ground” and had seen no evidences of the presence of the arch enemy, and that it could not be possible that there was lurking in the neighboring forests the murderous foe whose appearance they momentarily expected-all of which fell on deafening ears. The word was passed around that this fellow was a spy sent out by the enemy to disarm the fears of the settlers and put them off their guard-he should be summarily dealt with, and a conference was held pending his detention. Earnest words were spoken and opinions clashed as to what should be done with this fellow; but at length, after a thorough questioning and cross-questioning, and owing to the man’s apparent honesty, wiser council prevailed and he was allowed to proceed, but not without many suspicious glances following his movements as he proceeded westward down the hill.

In other parts of Ellington people were congregating and providing means of defense as best they could; women were engaged in running bullets and otherwise providing the sinews of war. It is said of one patriotic citizen, who, preferring military confinement to the unpleasant custom of scalp-lifting as practiced by the enemy, sought refuge in a hollow log, and there remained until the dusky twilight made escape more certain.

It was late in the afternoon before the struggling militia and armed citizens, who had planned to approach the enemy from the rear by way of Olds’ Corners, with strategic caution, arrived at the scene of the trouble and ascertained its cause. From here the news was quickly carried to the garrison on the hill of the false alarm, who in their exuberance of joy, discharged their firearms into the air, thus causing trouble and consternation among the women and children in the cellar, who thought the attack commenced, but their fears were soon put at rest and they were released from their confinement. Great was the anxiety aroused at this meeting, but greater by far was the joy of the parting of this heroic band, as they turned their backs upon the invisible foe and hastened to their weeping families; but the story kept going and the scenes here recorded were in a measure re-enacted at other points and in other localities more remote.

I cannot close this paper, however, without adding an article published in the Fredonia Censor of the date of January 17, 1838, concerning this affair, which, while faulty in many particulars, due no doubt to the difficulty of obtaining at that time the facts among so many conflicting rumors, yet it serves to more truly portray the extent to which the excitement prevailed among the people at that time throughout many of the eastern towns of the county. The article is head-lined:

“TERRIBLE WAR IN A NEW QUARTER.”

On Saturday, the 6th inst., several of the eastern towns of this county were thrown into the greatest consternation by a report that got into circulation that Three Thousand Indians from Canada had landed at the mouth of Cattaraugus Creek and had made their way into the region of the Conewango Valley and were pressing on, murdering and scalping everybody in their way. An express came to Sinclairville from the Colonel of the regiment there, under the greatest excitement, tears actually standing in his eyes. Immediately the rumor flew. All the old guns were instantly in requisition, many that had remained dumb for years, unless breaking silence at a squirrel hunt—the tea chests of all the stores were rifled for lead, which was immediately run into bullets—every ounce of powder in the place was bought and a team got up to send to this village for more. Directions were given to the families of those who were going to meet the enemy how to secure themselves and in short every preparation was made for a bloody encounter.

“In the Town of Arkwright the excitement and alarm was, if possible, still greater. During the afternoon and night families were flying from house to house, in some cases half a dozen families congregating together, the greatest dismay depicted on their countenances—horses were kept harnessed to wagons all night, ready for instant flight—weapons of defense of every kind were brought into requisition, the women assisting therein—one old lady, we are informed, run a hundred bullets. We are told the reason the express did not come through from Arkwright to this village was the intervention of about a mile of woods, into which he did not dare to penetrate for fear of being waylaid. A horse on one route we are informed, was actually rode to death.

“But our readers are probably anxious by this time to know what gave rise to all this hubbub, and we think it is time to inform them. Well, a drunken coot in the Village of Rutlege, which is situate on the eastern line of this county, having taken his usual deep potations, retired to the edge of a piece of woods and stretched himself out upon a log to sleep it off. A short time afterward one of bis children, a little girl, discovering him in this situation, and at the same time perceiving a little further on in the woods a couple of squaws, who were, however, peaceably employed in making brooms or baskets, ran home in great terror and told her mother the Indians had killed her father. The mother spread the alarm in the village with the usual accompanyments —the couriers were sent off and by the time they reached the next town the number of Indians were multiplied into three thousand! and from this simple circumstance arose all this foment that for twenty four hours kept the inhabitants in three or four towns in fear of instant death by merciless savages. And for the time being we suppose that neither ancient or modern history furnishes a parallel to it.

“The marvelous exploits of Sancho Panza upon the Island of Barrataria, the battle of the Kings, the memorable outbreak of the Windam frogs, when the sable African ran in terror to his master exclaiming, ‘Old Lucifer’s come and called for his crew, And you must go massa and Elderkin too,’ was not a priming to this Indian War. The next day, however, brought a little sober reflection, and with it a feeling not much more agreeable than that caused by their fears. Like the good people of Windham, we understand those infected do not wish to say a word upon the subject. We will, therefore, spare their feelings by stopping where we are.’

So this historic incident has ever since come to be spoken of by the few survivors of those days, as “The Indian War,” but to the present generation it is largely an unknown chapter in the county’s history.

________________

From “The Centennial History of Chautauqua County: a detailed and entertaining story of one hundred years of development”, New York, Vol II. pp 562-567, published by The Chautauqua History Company, Jamestown, New York, October 30, 1901.

Note: Copied verbatim–spelling and all.